Page Tables, Implementing Shebang, and Integer Overflow in Xv6

Introduction

xv6 is a reimplementation of UNIXv6 for x86 architecture, created by MIT to be used in their Operating System courses. I found it to be an absolutely great course and learned a lot from it. Hence, I wanted to write about it.

In this post, I will explain some of my solutions for the exercise questions posed in Chapter 2 of the booklet, namely the chapter Page Tables. Since the subject is presented extensively in the book, I won’t re-write every detail about it. Since xv6 is used as an actual course in many universities, I won’t be posting answers to the homework assignments, but only to the Exercise questions. For the record, I am referring to the Revision 10 of the booklet.

The contents of this post will explain:

- How to implement a

syscallto traverse a page table - How to implement a

Shebanginterpreter forExecto handle scripts - And how an

Integer Overflowmight be exploited to takeover kernel

Let’s get started.

Page Tables

1. Look at real operating systems to see how they size memory.

This question is answered thoroughly in the famous OSDev wiki. As it was stated in xv6, this really is a tricky thing to do in x86. Basically, our safest bet is to get the information from the BIOS. But how do we access to BIOS in protected mode, while the OS is running?

http://wiki.osdev.org/Detecting_Memory_(x86)

3. Write a user program that grows its address space with 1 byte by calling sbrk(1). Run the program and investigate the page table for the program before the call to sbrk and after the call to sbrk. How much space has the kernel allocated? What does the pte for the new memory contain?

To be able to investigate the page table easily, I wrote a system call which prints the page directory of the current process. Also, to understand some other problems I was curious about, I added a parameter to the system call, which acts like a switch and if it is set to 1, it prints the KERNEL pages, and if it is set to 0, it prints the USER pages. Here is the code:

//sysproc.c

int sys_traverse(void){

struct proc *p = myproc();

pde_t *pgtab;

int i, k, argument, flag = 0;

if(argint(0, &argument) < 0){

cprintf("no argument passed.\n");

return -1;

}

cprintf("p->name: %s\n", p->name);

cprintf("p->pgdir: %x\n\n", p->pgdir);

cprintf("argument: %d\n", argument);

for( i = 0; i < 1024; i++ ){

if( (p->pgdir)[i] & PTE_P ){ //(a == 1) ? 20: 30

flag = 0;

pgtab = (pte_t*)P2V(PTE_ADDR( (p->pgdir)[i] ));

for( k = 0; k < 1024; k ++){

if( pgtab[k] & PTE_P && pgtab[k] & ( (argument == 0) ? PTE_U: ( (pgtab[k] & PTE_U) == 0) ) ){

if(flag == 0){

cprintf("&p->pgdir[%d]: %x, p->pgdir[%d]: %x\n", i, &(p->pgdir)[i], i, (p->pgdir)[i] );

cprintf("\tpgtab starts at: %x and contains these entries:\n", pgtab);

flag = 1;

}

cprintf("\t\t&pgtab[%d]: %x, pgtab[%d]: %x\n", k, &pgtab[k], k, pgtab[k]);

}

}

}

}

return 0;

}xv6 Does not set the PTE_U bit in Page Directory Entries. That means, we cannot check whether the table belongs to USER or KERNEL in PDEs. So, I had to check this in PTEs. Hence, I summoned this ugly creature from the one-liner hell. Lesson learned: Don’t hesitate to use nested ifs, this is much uglier.

if( pgtab[k] & PTE_P && pgtab[k] & ( (argument == 0) ? PTE_U: ( (pgtab[k] & PTE_U) == 0) ) ){The first condition checks whether the PTE is present, the second condition checks if the argument asks for USER pages (i.e 0). If we are looking for USER pages, we do bitwise and on pgtab[k] with PTE_U. Otherwise, we check whether the PGTAB contains PTE_U bit and negate it by checking against 0.

Implementing the rest of the system call is unrelated to this post, so I will skip it. You can find some other blog posts detailing the necessary steps.

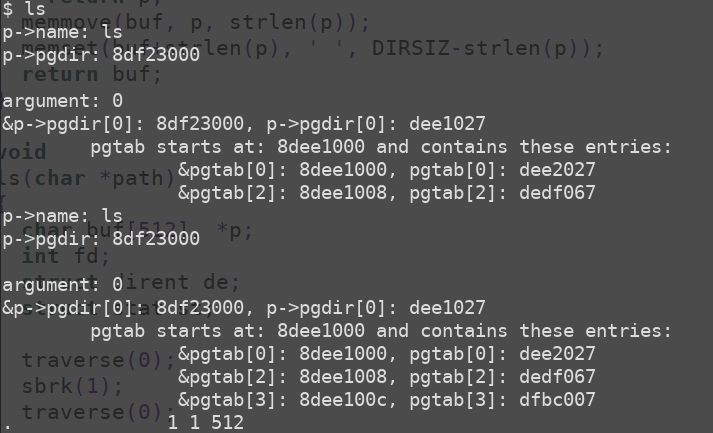

Now that we have a system call to traverse the page table, we can answer the question. xv6 Allocates another page for a 1 byte sbrk call. You can see it in the screenshot below.

Implementing the Shebang

5. Unix implementations of exec traditionally include special handling for shell scripts. If the file to execute begins with the text #!, then the first line is taken to be a program to run to interpret the file. For example, if exec is called to run myprog arg1 and myprog’s first line is #!/interp, then exec runs /interp with command line /interp myprog arg1. Implement support for this convention in xv6.

Before we get into the implementation of this, we need a script with a shebang line (#!/interp) so that it will be interpreted and we will be able to debug easily as we implement the code. In xv6’s main directory, I executed this to have a simple script with a visible result.

cat > script

#!/sh

echo hello;

ls;Then, we need to modify the MAKEFILE so that this script is included in xv6’s filesystem. Find the following line and modify it as shown below:

fs.img: mkfs README $(UPROGS) script

./mkfs fs.img README $(UPROGS) script

Great. Now when we compile xv6, we will see a file named “script” in xv6’s filesystem.

Implementing a shebang consists of two parts. First, we need to have this functionality present in our kernel. Only after that, user level programs can benefit from it and interpret the contents of the script. Since xv6 is a small system, only our beloved “sh” has the capability to interpret the script. To implement the functionality in the kernel, “exec.c” is our first stop.

//exec.c

char shebang[3];

char interp_path[16]; //16 is for historical reasons.

if(readi(ip, (char*)&shebang, 0, sizeof(shebang)) != sizeof(shebang))

goto bad;

shebang[2] = '\0';

if( shebang[0] == '#' && shebang[1] == '!' ){

//cprintf("shebang: %s\n", shebang);

readi(ip, (char*)&interp_path, 2, sizeof(interp_path));

//cprintf("interp_path: %s\n", interp_path);

for(i = 0; i < sizeof(interp_path); i++){

if(interp_path[i] == 0xa){

interp_path[i] = '\0';

break;

}

}

exec(interp_path, argv);

}The code is pretty much self-explanatory. We read the first 3 bytes of the file into a buffer and check whether the file starts with “#!”.

You might say “Hey, how do you know the file actually has 3 bytes? Won’t this cause some problems?” The answer is no because this functionality is implemented in “exec.c”, so we expect that the files that come here are either ELF files, whose header size is already bigger than 3 bytes, or script files, which start with “#!” bytes anyway.

Later, we read the first 16 bytes into interp_path variable, starting from the second byte into the file. Again, you might ask “Why 16 bytes? The interpreter path might be longer!” That is correct. However, xv6 is a remake of the legendary UNIX v6, and traditionally, interpreter path was assumed as 16 bytes in the first implementations. You can check the history of it from here:

https://www.in-ulm.de/~mascheck/various/shebang/

One last thing, “0xa” is the newline in xv6, so it is used to separate commands from the shebang line. After that, we are done in “exec.c”, so we call “exec.c” itself, with interpreter path as the file to be executed, and the script as the argument. Since interpreter path is the first argument, which is what ip points to, first two bytes will not be “#!”, instead it will be the interpreter’s ELF binary.

Now that we are done, let’s see the code we need to write in “sh.c” in order to interpret the actual script content.

//sh.c

if( (argc == 1) & strcmp(argv[0], "sh") ){

fd = open(argv[0], O_RDONLY);

if( fd < 0)

printf(1, "sh could not open: %s\n", argv[0]);

read_bytes = read(fd, buf, sizeof(buf));

script_start = strchr(buf, 0xa);

if( buf[read_bytes -1] == 0xa )

buf[read_bytes -1] = '\0';

if(fork1() == 0)

runcmd(parsecmd(script_start));

wait();

exit();

}At first line, we are checking whether the program has only one arguments and whether it is “sh”, shell’s name itself. If it is, we don’t have any arguments, so this condition will not be met and sh will continue executing normally. Otherwise, we have an argument which needs to be interpreted. We just read the file and since the rest of the functionality we need is actually implemented in xv6 itself, we just copy it from there.

One thing that I should mention is that I haven’t copied the code related to the “cd” command. If you want, you can copy it and modify the variables yourself.

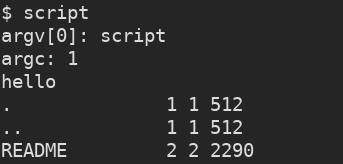

And this is all we need. Let’s just compile and run the script. The result is:

Integer Overflow

6. Delete the check if(ph.vaddr + ph.memsz < ph.vaddr) in exec.c, and con- struct a user program that exploits that the check is missing.

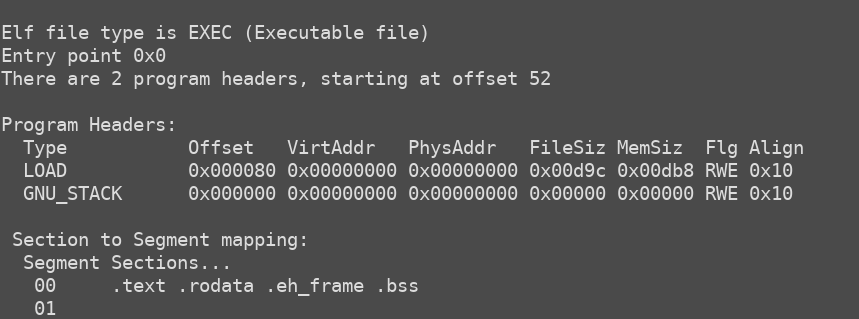

Even though this is the easiest question of all, I really liked this one. It perfectly demonstrates how an innocent looking integer overflow can be used to takeover the whole kernel. For this question, I used “ls” binary as the subject. To inspect how the program headers look lie on a normal “ls” binary, we can use “readelf -l _ls” in xv6’s main directory. The result is:

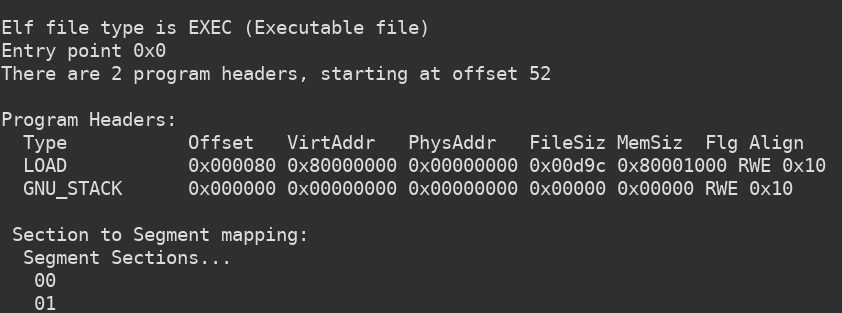

So, on an innocent program, obviously (ph.vaddr + ph.memsz) will never be smaller than ph.vaddr. However, if we craft a program header like below, and the check does not exist, the address can be anything we want, including kernel’s addresses. That way, we can overwrite kernel’s pages, effectively taking over the system.

You can modify the program header by opening it with a simple hex editor. I will not be showing how it is done, as there are already more than enough resources on that.

This post has already turned out to be longer than I anticipated, but just a quick shout out to the people at MIT for preparing such a great content and making it available to the public. Also, much thanks to the UNIX gods for this amazing OS + and the almighty C :)

Hope this post was as useful to you as it was to me. See you in another one.

Some references and useful resources:

http://wiki.osdev.org/Detecting_Memory_(x86)

https://github.com/YehudaShapira/xv6-explained/blob/master/xv6%20Code%20Explained.md

http://www.fotiskoutoulakis.com/2014/04/28/introduction-to-xv6-adding-a-new-system-call.html